Domain Name Disputes: An Introduction to Its Main Features

By Mihaela Maravela [1]

2 October, 2025

History of the UDRP

The Domain Name System (“DNS”) was developed to facilitate public access to web pages following the commercial development of the Internet starting with mid-1995, in contrast to its initial military purposes.

In absence of certain meaningful names, one needed to know and remember the Internet Protocol (“IP”) address for each website, which is formed of a series of numbers separated by dots (two identical Internet addresses cannot coexist, in virtue of the same rules according to which a telephone number can be allocated to only one telephone line). The transformation into letters and numbers via the DNS enables the IP address to be easily recognised and remembered.[2]

With the commercial use, the DNS came into conflict with the system of business identifiers that existed before the arrival of the Internet and that are protected by intellectual property rights, such as trademarks.

When business investments, advertising and other commercial activities increased on the Internet, it became clear to companies that problems may occur when a website using their trademark as a domain name was operated in an infringing manner without permission.

Disputes have rapidly increased, but in the late 1990s, trademark owners were incurring significant costs to protect and enforce their rights in relation to domain names, and were voicing a need for a clear, less expensive and enforceable system to protect their business online.

The costs were too high for brand owners and the procedures too lengthy and complicated, because of the inherent hurdles for efficient enforcement of intellectual property rights against abusive Internet domain name registrations: the Internet is multijurisdictional, as users can access it from any place on Earth. The global presence of the Internet and domain names might give rise to infringements of intellectual property rights in several jurisdictions.

In practical terms, this means that different national courts might assert jurisdiction to solve a dispute involving a domain name or that multiple proceedings should be initiated by a trademark owner that wants to protect its trademark in various jurisdictions where separate intellectual property titles might be claimed.

However, domain name disputes needed to be solved swiftly in view of the ease and speed with which an Internet registration may be obtained. There was a disproportion between the low cost of obtaining an Internet domain name and the high cost incurred by an intellectual property owner fighting an infringement before the courts of law.[3]

Another issue is that trademarks are territorially limited, with legal titles being granted following a regulated registration procedure, whereas domain names are globally effective, with technical addresses being instantaneously available on a first-come, first-served basis.

From both the consumer’s perspective and that of a trademark owner, having access to a quick system for solving disputes involving abusive registration of domain names was and is still key.

In these circumstances, the procedure provided by the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (“UDRP” or “Policy”) was adopted in October 1999 by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (“ICANN”) following a process initiated by the World Intellectual Property Organization (“WIPO”).

Jurisdiction in Domain Name Disputes

The UDRP is used to resolve domain name disputes for all generic top-level domains (“gTLDs”), including the new gTLDs, and also for a number of country-code top-level domains (“ccTLDs”), in certain cases as a modified version of the UDRP.

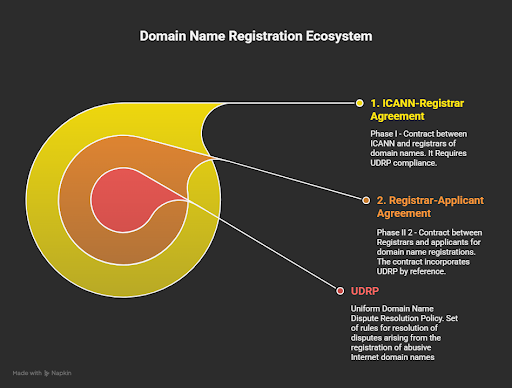

As with arbitration, consent is the cornerstone of the administrative proceedings for domain name disputes. It resides in a contract.

The difference from arbitration is that in the case of domain name disputes, there is no contract between the parties to the dispute. Rather, in the case of the UDRP, there is a set of contractual relations that binds together the participants in the Domain Name System.

A first contract is the contract between ICANN – which accredits registrars to accept registrations of domain names – and the registrars. The terms of such contractual accreditation require the registrars to respect the decisions of panels under the UDRP and to require persons who apply to them for domain name registrations to also comply with the UDRP.

A second contract is between registrars and applicants for domain name registrations. The UDRP is incorporated by reference into the registration agreement entered into between each domain name holder and the registrar.

By means of such a registration agreement, any domain name holder (for all gTLDs and some ccTLDs), must defer to a mandatory administrative proceeding dealing with claims of abusive domain name registration (cybersquatting).

Therefore, from the outset, the registrant accepts that in case a third party, who claims that its trademark right was breached by the registration of the domain name, initiates UDRP proceedings, the registrant will accept to be a party to the proceedings and will be bound by the decision, without access to courts being denied.

ccTLDs: An Exception to the Rule

As mentioned, ccTLDs and gTLDs are the two foundational building blocks of the Domain Name System. When talking about domain names, most are familiar with endings such as .com, .net, .org and similar “generic” TLDs, and fewer would know the distinction between ccTLDs and gTLDs. ccTLDs are the two-letter endings of domain names based on the ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 country list[4] assigned to countries or territories, such as .de for Germany, .fr for France, .jp for Japan or even .ai for Anguilla. Initially administered on a volunteer or university-based model, many ccTLD registries have since evolved into national institutions or delegated private operators, governed by local laws. They play a key role in digital sovereignty, offering tailored domain policies and representing a form of "national infrastructure" on the global internet.

While some ccTLDs have adopted the UDRP or modified versions of it, many others maintain different alternative dispute resolution procedures (such as .fr (France) with their recent introduction of a mediation procedure in their Alternative Dispute Resolution) or court litigation (such as .de (Germany)).

What Type of Disputes Are Covered under the UDRP

The UDRP is designed for the resolution of disputes arising from the registration of abusive Internet domain names infringing upon rights of trademark owners (cybersquatting), where the following conditions are cumulatively met:

1. the domain name registered by the domain name registrant is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the complainant (the person or entity bringing the complaint) has rights;

2. the domain name registrant has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name in question; and

3. the domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

Differences Between UDRP and Arbitration/Court Disputes

The UDRP procedure is a sui-generis alternative dispute resolution procedure, or as often called, an administrative procedure, because, unlike arbitration, UDRP proceedings expressly allow recourse to national courts, while arbitration results in a final and binding decision that can be enforced against the unsuccessful party.

Also, (i) as mentioned above, there is no arbitration agreement between the parties to the dispute in the latter process; rather, the procedure is based on the domain name registrant’s consent given in the registration agreement of the domain name; (ii) the decision issued by an administrative panel does not need to be enforced in a court of law; rather, the registrar of the domain name has to enforce the decision based on its contractual obligation to ICANN, as the accrediting body; (iii) courts of law are not bound by UDRP decisions, as they are by arbitral awards; court proceedings can be initiated any time with the case being heard once again.

Moreover, in the UDRP process there are no hearings, no discovery, and no witness examination.

Compared to court litigation, the administrative procedure developed under the UDRP takes less time (2-3 months) instead of years of litigation, is based only on written submissions, and is directly enforceable by the registrar once a 10-day term from the decision elapses without the need for initiating court litigation.

Procedural aspects, such as consolidation of domain name disputes, language of proceedings, unilateral consent to transfer - all aim at efficiency of the process, complainants seeing their cases solved in 2-3 months, which is a clear advantage to court systems where it could take years to get a final result.

Domain Name Disputes and the Jurisprudential Principles Developed Under It

The UDRP provides for a swift mechanism in terms of applicable law, as the Policy was designed to operate in a global context.

Even if the applicable principles have roots in trademark laws, proving a case does not generally require litigating over specific national laws, rather resorting to the principles developed under the UDRP case law, as a set of transnational rules apt to solve cybersquatting cases was developed, that takes due regard to the nature of Internet: “there is no ‘there’ there”.

In certain cases, recourse to national laws is needed.

For example, in terms of proving trademark rights, specific situations might trigger discussions under relevant national laws, such as whether the trademark is indeed registered, or if it can ground a UDRP complaint absent a finalized registration, or whether the complainant can show unregistered or common law rights in a trademark.

Also, national laws might become relevant in the so-called “gripe site” cases, where the owner of a certain domain name deliberately uses a protected trademark to criticize the trademark holder (e.g. “sucks cases”). In addition, national laws might become relevant to assess if a trademark was registered prior to the registration of the domain name, to determine if the domain name was registered in bad faith.

Even if the decisions of UDRP panels are not binding precedents,[5] they do have precedential authority.[6] In practice, they are largely followed depending on the specifics of the case, which ensures consistency, predictability and fairness of the UDRP system.

UDRP decisions are published. This responds to the plea for more transparency in international arbitration, as greater transparency of procedure and outcome ultimately benefits all stakeholders: the arbitrators, who can rely on established standards and contribute to their development, parties and their representatives who profit from increased predictability and legal certainty before and during the proceedings and – last but not least – arbitral institutions who can create trust and provide evidence that arbitral proceedings are conducted in accordance with professional standards and the rule of law.[7]

Institutions that Administer UDRP Disputes

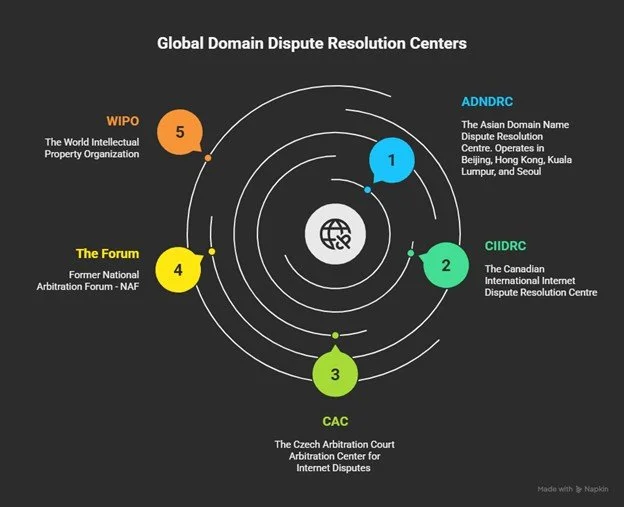

The providers of services under the UDRP approved by ICANN are:

The Asian Domain Name Dispute Resolution Centre (ADNDRC). ADNDRC operates four offices: Beijing (operated by CIETAC), Hong Kong (operated by HKIAC), Kuala Lumpur (operated by the Asian International Arbitration Centre (“AIAC”)), and Seoul (operated by the Korea Internet Address Dispute Resolution Committee (“IDRC”)). Each office of ADNDRC provides services concerning gTLDs, new gTLDs, and certain ccTLDs;

The Canadian International Internet Dispute Resolution Centre (CIIDRC);

The Czech Arbitration Court Arbitration Center for Internet Disputes (CAC);

The Forum (former National Arbitration Forum - NAF);

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

There are also jurisdictions where domain name disputes can only be solved before courts of law, such as Russia or Germany.

In other jurisdictions, domain name disputes are solved by arbitration, resulting in a final and binding decision. As an example, Article 4 of the Hong Kong Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy states that the parties are required to submit to a mandatory arbitration proceeding which is governed by the Hong Kong Arbitration Ordinance. The award rendered is therefore not subject to appeal in any court and is considered as an arbitration award rendered in Hong Kong for the purpose of enforcement under the New York Convention.[8]

Another example is for the .pl (Poland) domain names, where for disputes where both parties are registered or resident outside Poland, the applicable policy is a slightly adapted version of the WIPO Expedited Arbitration Rules.

Background and Qualifications of Domain Name Panelists

The decision makers are called panelists and are reputed individuals with experience in trademark laws and international disputes. The pool of professionals is diverse and appointments are made to take into consideration a diverse distribution of cases.

The panelists sign a statement of impartiality and independence toward the parties in dispute to avoid conflicts of interest, similar to arbitrators.

Final Remarks

Although not arbitration per se, the UDRP implemented 25 years ago elements that are now explored in international arbitration to respond to increased criticism as to lack of transparency, lack of predictability, and lack of diversity.

Given all these advantages, there is no doubt that the UDRP is here to stay, as Internet safety depends on such a swift and predictable system of dispute resolution.

________________

About the author:

Mihaela Maravela is a Partner lawyer with Mihaela Maravela Law Office in Bucharest, Romania (member of Maravela Codescu Buliga Attorneys at law). She is an experienced counsel in arbitration, acting under numerous rules, such as ICSID, UNCITRAL, ICC, VIAC, WIPO, CICA-CCIR Rules.

Mihaela sits as arbitrator in domestic and international commercial arbitration and she solved +10 domestic and international commercial arbitrations. She also sits as domain name panelist and she solved over 340 UDRP disputes at the World Intellectual Property Organisation.

She is ranked as a Global Leader in Arbitration and Trademarks since 2018 by Lexology (former WWL).

Mihaela is also experienced in various business sectors such as corporate, M&A, finance & banking, infrastructure, intellectual property, energy, oil & gas, environmental and climate change.

________________

[1] Editors: Stefanie Efstathiou (Independent Practice) and Mihaela Apostol (ArbTech)

[2] Mihaela Maravela, Chapter 7.02: RO Domain Name Disputes in Romania, in Arbitration in Romania, a Practitioner’s Guide, Crenguța Leaua and Flavius A. Baias (eds), Wolters Kluwer, 2016, p. 436.

[3] Georg von Segesser and Aileen Truttmann, 'Chapter 12: Swiss and Swiss-based Arbitral Institutions', in Elliott Geisinger and Nathalie Voser (eds), International Arbitration in Switzerland: A Handbook for Practitioners (Second Edition), 2nd edition (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2013), p. 290.

[4] Postel, J. (1994). Domain Name System Structure and Delegation. RFC 1591. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc1591

[5] Andrea Mondini, 'Chapter 3: The Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy', in Laurent Lévy and Michael Polkinghorne (eds), Expedited Procedures in International Arbitration, Dossiers of the ICC Institute of World Business Law, Volume 16 (© Kluwer Law International; International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) 2017), p. 80.

[6] Gary B. Born, 'Chapter 27: Preclusion, Lis Pendens and Stare Decisis in International Arbitration', in, International Commercial Arbitration (Second Edition), 2nd edition (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2014), pp. 3823-3824.

[7] Philip Wimalasena, 'The Publication of Arbitral Awards as a Contribution to Legal Development – A Plea for more Transparency', in Matthias Scherer (ed), ASA Bulletin, (© Association Suisse de l'Arbitrage; Kluwer Law International 2019, Volume 37 Issue 2), pp. 287 – 288.

[8] The United Nations Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards of 1958. See Derric Yeoh, ‘Is Online Dispute Resolution The Future of Alternative Dispute Resolution?’, Kluwer Arbitration Blog, March 29 2018, http://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2018/03/29/online-dispute-resolution-future-alternative-dispute-resolution/.