Transforming Multi-million Data Points Into a Snapshot of the Arbitration World

15 October, 2025

ArbTech interview with Dr. Thomas Lehmann

After conducting 117 interviews over 70+ hours and engaging extensively with the arbitration community, Dr. Thomas Lehmann shifts from interviewer to interviewee. In this conversation, we delve into the making of the 2025 International Arbitration Survey, led by the School of International Arbitration at Queen Mary University of London in partnership with White & Case. From drafting and refining the questions to gathering millions of data points and distilling them into a clear snapshot of the arbitration landscape, Thomas shares insights into the process, and focuses on the big question: How does the arbitration community view technology? We explore key concerns and reflect on a few ideas about the future.

Mihaela Apostol (ArbTech): A good place to begin is with an introduction to the survey and its key findings, particularly those related to the role of AI in international arbitration. Could you provide more information about the 2025 International Arbitration Survey?

Dr. Thomas Lehmann: The 2025 International Arbitration Survey: ‘The Path Forward: Realities and Opportunities in Arbitration’ is the fourteenth major empirical International Arbitration Survey conducted by the School of International Arbitration, the sixth in partnership with White & Case. For the 2025 edition, I was responsible for collecting survey responses, analysing the data, conducting interviews, and drafting the report, all under the guidance and review of my supervisors at Queen Mary University, Norah Gallagher Dr. Maria Fanou, the lead investigators on the research project.

The Survey considers both current practices and future opportunities for the system of international arbitration, as well as key aspects of the arbitral process, as experienced by its users. The Survey gathered the views of the international arbitration community globally, including private practitioners, in-house counsels, arbitrators, academics, arbitral institution staff, tribunal secretaries, experts, and service providers.

Mihaela: It sounds like an incredibly complex undertaking. Where does one begin? Could you walk us through the overall process of designing the Survey?

Thomas: It all starts with a team effort in designing the questionnaire. The Survey is widely relied upon by arbitration practitioners and is sometimes cited before arbitral tribunals. Precise wording was paramount in designing the Survey questions. Hundreds of hours were dedicated to refining the ideas behind each question put to the arbitration community. Overall, the questionnaire was designed through an iterative process by selecting relevant topics, carefully crafting each question-and-answer options, and amending the wording to the highest standard possible.

An external focus group, comprising experienced arbitration practitioners and academics, helped us identify gaps and/or wording that could have potentially caused uncertainties or raised questions. A significant emphasis was put on streamlining questions to clarify the content of the Survey. This ensured it was quick and easy for our busy respondent community to complete. The aim was also to reduce the phenomenon of ‘survey fatigue’, by which the share of respondents drops from question to question. This was successfully prevented, with each question in the Survey receiving at least 88% of responses from the respondent pool.

Mihaela: The process you have described sounds very similar to preparing for a hearing and crafting cross-examination questions. When reading the results, everything appears very easy, but in reality, there is a great deal of strategy and effort behind them. I imagine a key element was the data collection process, what did that involve?

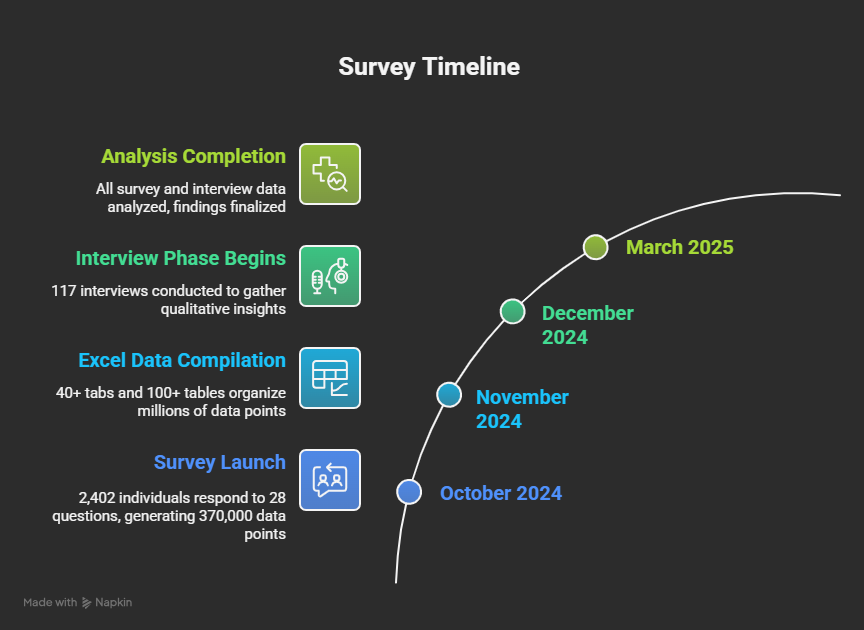

Thomas: Data collection was a gigantic task. It took approximately five months to gather the data, insert it into anonymised and readable Excel sheets, break it down, create tables, and eventually analyse the outcomes.

The Survey received 2,402 individual responses to 28 questions, many of which offered the possibility of choosing from multiple answer options and free-text boxes (for example, the person’s occupation, preference for regional seats, or institutions). The answers to the 28 questions alone represented 370,000 data points in a single table. The data for each question was also broken down by role, experience, and region and further combined data outputs.

The result was an anonymised Excel document with 40-odd tabs, over 100 tables, and millions of data points.

As for interviews, 117 were conducted from the end of October 2024 until March 2025. Interviewees were contacted based on their consent to participate in the interview, which they provided during the Survey. Reflective of the respondents’ pool, the majority of interviewees were counsel and arbitrators, but there were also several in-house counsel, institution staff, experts, arbitral secretaries and academics. Each interview with a respondent was meticulously prepared to ensure relevant questions were raised. Interviewees were generous with their time and displayed a wide range of expertise, for instance, on novel topics such as Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Mihaela: It sounds like you reviewed a massive amount of information and now have unique insights into the key issues shaping the arbitration community. AI is certainly one of them, hardly any major arbitration event takes place without an AI panel. Based on the Survey results, what key insights emerged about the role and perception of AI in international arbitration? Are practitioners concerned about AI?

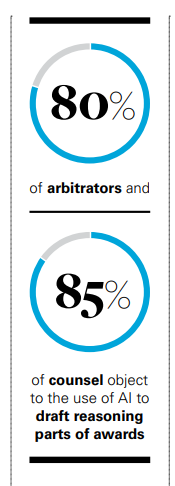

Thomas: It is very natural to react with fear to new technologies. The arbitration community expressed cautiousness, concerns, and optimism towards the adoption of AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) in arbitration. Some interviewees expressed blunt viewpoints on the uselessness of LLM tools for international arbitration, while others offered imaginative ways of integrating AI in their daily work (e.g., in summarising reports or technical expert evidence, finding evidence buried in thousands of emails, helping draft emails or redundant parts of submissions). Most interviewees, nevertheless, considered that AI cannot replace good lawyering, and most were concerned with confidentiality issues, as well as the risk of hallucination by LLMs. Many expressed concerns about the legal education of the younger generation and the prospect of tribunal secretaries competing with AI.

Mihaela: So there is a mix of optimism and concerns. Were there any surprising or unexpected findings related to AI?

Thomas: The sheer number of respondents preparing for AI and LLMs to integrate their workflow was surprising. Arbitration practitioners, especially younger ones, seemed “ready for change”. I would even say that most practitioners are open to the inclusion of AI in their work, provided that ethical standards are not compromised. [1]

Mihaela: After reviewing so many answers and discussing with a lot of interviewees, how has your own perception of AI in arbitration evolved as a result of this project?

Thomas: AI has clear benefits for international arbitration. It can expedite proceedings, enhance the efficiency of certain discoveries, and facilitate the review of footnotes or specific sentences. However, common generative LLMs, such as ChatGPT, have no future in arbitration. Those will be replaced by dedicated AI tools designed for lawyers and grounded in international law and arbitration sources.

AI and LLMs also carry clear, albeit not immediate, dangers. While AI is not inherently menacing, the danger lies in practitioners gradually delegating decision-making to AI. This would engender the risk of “reducing brain activity and memory”, potentially increasing risks of cognitive atrophy, and eventually impacting the quality of parties’ submissions and even arbitral awards themselves. In fact, several interviewees expressed the idea that AI and LLMs could impact the mental processes required for decision-making, noting that drafting is a continuous decision-making process.

On the one hand, if unchecked, AI can do greater harm than good to the field of international arbitration by affecting cognitive processes for decision-making, as well as the quality of submissions and awards. On the other hand, AI can be an excellent efficiency-booster for specific tasks, for which proprietary LLM models and legal search engines grounded in the right and accurate data could be particularly helpful.

Mihaela: Despite the cost-efficiency benefits, AI is still not integrated at a larger scale. What do you believe are the most pressing needs to address current concerns around AI in arbitration?

Thomas: Education is the word coming to mind. When AI is used correctly, it is helpful and does not pose a risk in and of itself. At the same time, practitioners overall, and particularly students, must learn about the limitations of AI and LLMs. Hallucinations are built into AI, which is not made to respond to a request with an “I don’t know” response. LLMs are designed to generate an answer, any answer.

The quality of the data is the second one. AI is not Google, nor Wikipedia. It entirely relies on the data it scrapes from the internet or that is given to it. It is therefore crucial that practitioners relying on AI or LLM (e.g., to search case law, review, or draft submissions) ensure these are properly trained on the best possible arbitration-related data and minimise the “noise” from other sources.

Ensuring law firms choose the right AI business models is a third consideration. Right now, AI companies (such as ChatGPT by OpenAI) operate on an “attention economy” model. They compete for users’ time and engagement.

For AI and LLMs to be truly effective legal tools, law firms should favour smaller-scale models built on a carefully curated pool of high-quality data.

“To keep people entertained and active, large language models may exaggerate or “glorify” whatever ideas, questions, or phrases users put to them. If asked, AI models will regard your painstakingly crafted legal argument with the same awe they reserve for a teenager’s poetry homework.”

Mihaela: Definitely a world of possibilities. How do you envision the role of AI evolving in international arbitration over the next few years?

Thomas: Law firms are starting to acquire AI models for specific tasks - in particular, discovery and AI-boosted legal research. This will certainly accelerate.

Arbitration clients will also certainly push for greater speed and efficiency. Some will actively encourage their counsel to use AI to “speed up the process,” at the expense of quality. In the same way, I can imagine counsel and users tolerating the use of AI by arbitrators, but launching annulment proceedings left and right if suspicions of intolerable use arise. On another note, even though the use of AI may lead to greater efficiency, I don’t expect fees to be brought down by law firms.

One can also foresee misuse of LLMs by certain practitioners, with hallucinations as the revealing mark. In a field resting on reputation, we can expect most practitioners to review written outputs. However, younger or busy practitioners may be tempted to rely on AI to produce faulty research, which could impact the submissions produced by an entire team.

Mihaela: This has been a fascinating journey for you, from crafting questions to analysing vast amounts of data and engaging with so many people across the arbitration community. How has working on this Survey shaped you as an arbitration professional?

Thomas: I really enjoyed my time as a researcher and interviewing highly regarded (and sometimes very witty) practitioners.

Interviewing experienced practitioners and users was initially intimidating. They expect to take part in one of the most highly regarded empirical research in international arbitration. Much time was therefore spent in preparing each interview, to produce interesting questions, listen to decade-shaped insights, and produce a reliable and qualitative report.

As an academic, I acquired strong skills in empirical research, data analysis and reporting. As a practitioner, I have honed my skills in questioning (cross-examination), semantic analysis, and clear expression.

Mihaela: I assume that, beyond gaining detailed insights into key arbitration topics, you also developed valuable technical and analytical skills through this project, skills that will no doubt serve you well in both your academic and professional career.

Thomas: Condensing 2402 answers and 117 interviews into one report was not an easy task. It was all about concision and clarity. The areas where I developed my skills the most were designing an accessible yet precise questionnaire, producing readable datasets, and crafting a clear report, which tries to strike a balance between comprehensiveness and conciseness.

If there is one skill I should single out, though, it is producing the most objective report while carefully considering even the most divergent viewpoints. Given the sometimes antagonist perspectives expressed by the practitioners, each task related to the Survey required exercising the greatest of nuance. I did my best and the report greatly benefited from the wisdom of Norah Gallagher and Dr. Maria Fanou in the review process.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this interview are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of Queen Mary University of London, White & Case LLP, or any other institution or individual associated with the 2025 International Arbitration Survey: ‘The Path Forward: Realities and Opportunities in Arbitration’.

Dr. Thomas Lehmann is a French Avocat and research fellow at the National University of Singapore. He was the research fellow for the “2025 International Arbitration Survey - The Path Forward: Realities and Opportunities in Arbitration”. Thomas has worked with and advised leading international arbitration teams and arbitrators in London and Paris.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[1] See also Melissa Heikkilä, Mitchell, Margaret, “Margaret Mitchell: artificial general intelligence is ‘just vibes and snake oil’”, Financial Times, 19 June 2025, available here: https://www.ft.com/content/7089bff2-25fc-4a25-98bf-8828ab24f48e [paywall]. See Simon Mundy, “Profit vs humanity: AI’s corporate governance debate”, Financial Times, 9 May 2025, available here: https://www.ft.com/content/78139990-33f3-428b-a07c-422e3dd1b702, referring to the AI developers' fiduciary obligations to the wider society.